By Hitesh Chugh, Associate

An international public health emergency is fortunately rare. The World Health Organisation (WHO) declared the first "public health emergency of international concern" in 2009 with the outbreak of H1N1 Swine Influenza. Further declarations were made for the extraordinary resurgence of Polio in 2014, and the devastating Ebola outbreak in West Africa, also in 2014.

Now, with Brazilian authorities estimating between 500,000-1,500,000 cases[1], the WHO has declared the Zika virus a threat of very serious proportions. In the wake of the West African Ebola crisis, and with the upcoming 2016 Rio Summer Olympics, the WHO is not in a position to take this threat lightly.

Zika is characterised by its mild symptoms including fever, rash, inflammation, malaise, and joint pain, lasting up to a week. However, the international concern over this virus is because of the circumstantial links to microcephaly – infants born with undersized heads - and Guillan-Barre syndrome (GBS)[2].

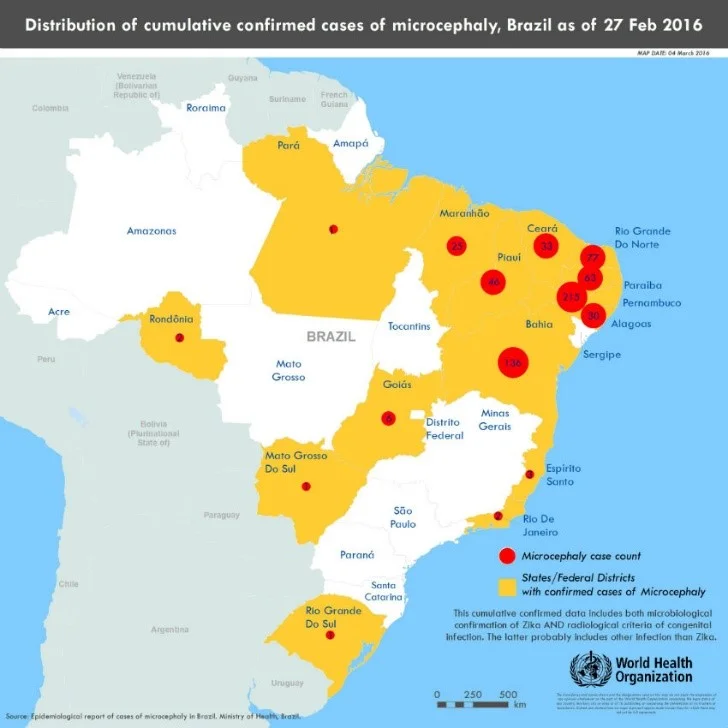

By February 2016, there were a total of 641 confirmed cases of microcephaly and 1708 confirmed cases of GBS. However, over 4000 suspected microcephaly cases remain under investigation. Due to the increasing magnitude of the disease, Brazil has stopped counting cases of Zika[3].

In effect, it is the potential for devastating generational consequences – the magnitude of which we are still unsure about - that is driving international fear.

Figure 1 - Distribution of microcephaly cases in Brazil

Global Response

Since 1952, when the first human case was identified in Uganda, Zika has steadily been spreading to the Pacific Island nations west to the Americas through the bite of an infected Aedes Aegypti mosquito. This is the same mosquito that transmits chikungunya, dengue fever and yellow fever. Currently, 47 countries have reported transmission or indication of transmission.

The global response is being guided by the Zika Strategic Response Framework & Joint Operations Plan. This framework highlights surveillance, response and research as the foundation to the international response. It provides support to affected countries, strengthens their capacity to prevent and control further outbreaks, and facilitates rapid research to better understand the virus and its effects.

The message thus far has been for pregnant women to avoid travelling to Zika affected areas, and has been complemented by international travel warnings and distribution of pregnancy management information.

In the absence of confirmed links to congenital birth defects, the Brazilian government conducted their largest health promotion campaign, enlisting over 200,000 troops to conduct door-to-door walks handing out information leaflets and mosquito repellent[4].

Australia’s Response

Figure 2 - Notifications of Zika in Australia (National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System – 9/03/2016)

Since the start of the outbreak, there have been 38 cases of Zika in Australia[5], the majority of which have been in Queensland. All these notifications are of Australians acquiring the infection overseas, not locally. The concern here is the large aedes aegypti population that thrives in tropical climate North-East Queensland - which historically has been responsible for multiple Dengue fever outbreaks.

The Queensland government has directed over $1 million for a public information campaign centred on mosquito control. This has been complemented by a $400,000 injection in their Townsville research laboratory dedicated to rapid Zika testing, and a public health spraying campaign in areas where a positive case is returned[6].

While evidence suggests that local transmission is unlikely, experts haven’t discounted the possibility that it may happen in the future.

Chief Health Officer Jeannette Young has stated that “[while] experts have reassured us that the risk of a Zika outbreak is very, very low, we do need to be prepared”.[7]

Moving forward

Testing to confirm links between the Zika virus and microcephaly continues, cases numbers are increasing, its distribution is widening, no vaccine is available, and the Olympics continue to loom.

All the while, British bio-technology firm Oxtiec are testing the use of genetically-modified mosquitoes to control the aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Their studies have shown that in the target area, their mosquitoes have decreased the population of the native aegypti population to below the threshold for disease transmission – nearly 95%[8].

The success of this trial in the city of Pracicaba has prompted the study’s escalation to larger mosquito control projects around Brazil to combat the spread of this virus.

Till then, the WHO will continue to work with affected countries to identify causal links with its suspected complications and control the outbreak.

What should I do?

Zika has only been brought to Australia by travellers, however the Aedes mosquito lives in northern Queensland and anyone diagnosed with Zika virus is advised against travel to north Queensland until they have cleared their infection. Women who are pregnant or who are planning to become pregnant, should consider delaying their travel to areas with active outbreaks of Zika. If you are travelling you should follow the advice at Smartraveller.

References

[1] http://www.who.int/emergencies/zika-virus/en/

[2]http://www.who.int/emergencies/zika-virus/en/

Guillan-Barre syndrome is a rare condition in which a person’s immune system attacks their peripheral nervous system. The syndrome can affect the nerves that control muscle movement as well as those that transmit feelings of pain, temperature and touch. This can result in muscle weakness and loss of sensation in the legs and/or arms. The cause of GBS cannot always be determined, but it is often triggered by an infection and less commonly by immunisation, surgery or trauma.

[3] http://www.who.int/emergencies/zika-virus/situation-report/4-march-2016/en/

[4] http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-latin-america-35566111

[5] http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/ohp-zika-notifications.htm

[6] https://www.health.qld.gov.au/news-alerts/health-alerts/zika/docs/virus_information/english.pdf

[7] http://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-02-04/rapid-testing-for-zika-virus-townsville-awareness-campaign/7141572

[8] http://www.oxitec.com/press-release-oxitec-mosquito-works-to-control-aedes-aegypti-in-dengue-hotspo/